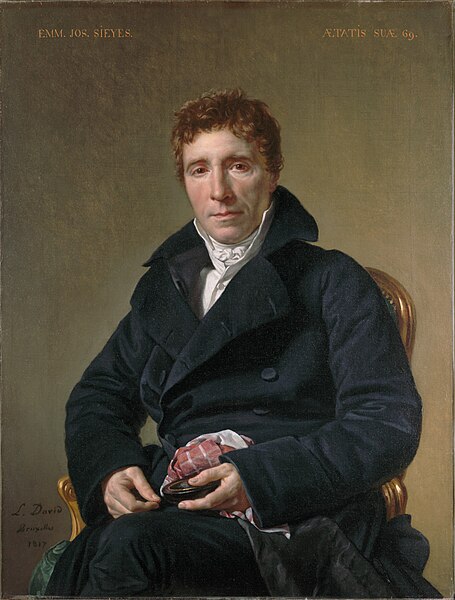

History is often shaped by the minds of schemers, but it is rarely they who seize the moment. The Coup of 18 Brumaire which was conceived by Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, executed by Napoleon Bonaparte, and saved by Lucien Bonaparte. It was supposed to be an elegant restructuring of power. Instead, it became a chaotic, theatrical seizure of authority.

Sieyès, the revolutionary thinker, had long dreamed of dismantling the crumbling Directory and replacing it with a strong but controlled government—one in which he would quietly hold the reins. But he never wanted Napoleon as his champion.

Sieyès’ Original Choice: The General He Never Got

Sieyès understood that a coup without military backing was doomed. He needed a general—one popular enough to command loyalty, yet pliable enough to remain under his influence. Napoleon Bonaparte was not his first choice.

Initially, Sieyès had considered General Barthélemy Catherine Joubert, a respected but relatively subdued military leader. Joubert, unlike Napoleon, lacked political ambitions and had the temperament of a soldier rather than a statesman. For Sieyès, this was ideal—a strong arm, not a strong mind.

But fate intervened. Joubert was killed in battle at Novi on August 15, 1799. This left Sieyès with no immediate alternative, and the pressure to act was growing. The Directory was collapsing, France was restless, and a power vacuum was forming.

It was then that Talleyrand and other political insiders persuaded Sieyès to consider Napoleon. Though Sieyès distrusted the young general’s ambition, Napoleon had three undeniable advantages:

1. Immense Popularity – His victories in Italy and Egypt had made him a national hero.

2. Loyalty of the Army – The military would follow him unquestioningly.

3. Political Naïveté (or so Sieyès believed) – Having spent much of his time on foreign campaigns, Napoleon was expected to be politically inexperienced, making him easier to control.

Reluctantly, Sieyès agreed. He believed he could use Napoleon as his instrument. But Napoleon was never an instrument—he was a force.

_________

Phase One: Sieyès Clears the Board

On 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799), the first act of the coup unfolded.

The Council of Ancients, already manipulated by Sieyès, declared a state of emergency due to a fabricated Jacobin threat. This allowed the government to be relocated to Saint-Cloud, removing the deputies from Paris and their usual sources of support. It was a masterstroke—isolate the legislature, control the narrative, eliminate opposition.

Meanwhile, Sieyès and his allies neutralized the Directory from within. Barras, corrupt and self-serving, was bribed into resigning. Sieyès and Roger Ducos stepped down voluntarily, leaving only two remaining Directors: Gohier and Moulin. When they refused to resign, Napoleon’s troops placed them under arrest.

By the evening of 18 Brumaire, the Directory was dead. Sieyès’ plan was unfolding exactly as intended.

——

Phase Two: When Napoleon Nearly Lost It All

If Sieyès envisioned a smooth transition of power, Napoleon was about to turn it into an outright takeover.

On 19 Brumaire (November 10, 1799), the Council of Ancients, still under Sieyès’ influence, accepted the coup with little resistance. The real test was the Council of Five Hundred, the lower house of the legislature.

Napoleon, expecting an easy reception, walked into the chamber of the Five Hundred unannounced. It was a mistake. The deputies immediately recognized what was happening, and chaos erupted.

Cries of “Down with the tyrant!” filled the air. Some deputies even physically attacked Napoleon. Startled, uncertain, and unprepared for this level of resistance, Napoleon panicked. He stammered, failed to control the room, and was physically pulled out by his own guards.

For the first time, the coup was in danger. The political machinery Sieyès had built so carefully was slipping out of control. Napoleon had failed in the chamber, and the coup was on the brink of collapse.

Lucien Bonaparte: The Brother Who Saved the Coup

This was the moment that Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon’s younger brother, changed history.

Lucien, the President of the Council of Five Hundred, saw the situation spiraling into disaster. But instead of retreating, he acted. Stepping outside, he mounted a horse, turned to the soldiers, and declared:

“My brother is in danger! The Council of Five Hundred has been infiltrated by assassins!”

This was a complete fabrication, but it worked. Napoleon’s soldiers, fiercely loyal to him, stormed the chamber with fixed bayonets. The deputies screamed, fled, and jumped out of windows. The Council of Five Hundred, once the last obstacle, was broken by sheer force.

The Aftermath: Napoleon Takes It All

By nightfall, a small, handpicked group of deputies was gathered to “legally” approve the formation of a new government. The Consulate was born. But while Sieyès had expected to rule from the shadows, Napoleon had other plans.

Within days, Sieyès was outmaneuvered. The new constitution placed Napoleon as First Consul, a position of near-total control. Sieyès, the supposed mastermind of the coup, was pushed into irrelevance.

He had spent years shaping France’s revolutionary ideals, but in the end, he had merely paved the way for a new dictatorship. He was rewarded with a grand estate, but his dream of guiding France’s future was gone.

Conclusion: The Coup That Became a Takeover

The Coup of 18 Brumaire was meant to be Sieyès’ revolution. He had designed it, orchestrated it, and set every piece in place. But the moment he brought Napoleon into the equation, he lost control of his own creation.

Sieyès had sought a controlled transition—Napoleon delivered a military seizure. Sieyès wanted a constitutional balance—Napoleon gave France an autocrat.

In the end, Sieyès planned the coup, but Napoleon took the throne.